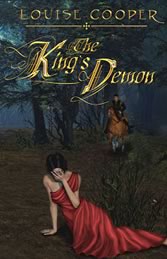

THE KING'S DEMON

**BUY NOW**

The young woman stumbling alone along a moorland road at dead of night, cowed and terrified by a thunderstorm, can remember nothing. The only fleeting image she has is of being imprisoned in a closed and windowless carriage, and knowing that, when it reached its destination, her captors were going to kill her. When she is almost run down by a fast-moving horse, she has no choice but to accept its rider's offer of help. But she doesn't trust him. And when he takes her to a desertedand isolated tower, where he says they will shelter until the storm is over, her misgivings grow by the minute…

When the lantern light spilled into the room above the stable she stared about

her with a mixture of curiosity and disappointment. Whatever this place might

be it was certainly no one's home, for the chamber that formed the tower's

upper floor was furnished only with a narrow bed, a table, stool, two chests,

and a rack of wooden shelves containing a cooking pot and two half burned candles.

There was a brazier in the middle of the room but it was dead and empty, and

the atmosphere was one of cold, dank disuse.

Her companion set the lantern down on the table, surveyed the room briefly

and said a word that she didn't recognise but which sounded like an extreme

profanity. 'Damn the keepers! It must be months since anyone was last here,

and they've not troubled to replenish any of the stores. . .' He took three

strides to one of the chests, wrenched it open and started to rummage among

the contents. Another profanity, and he slung a bundle of thin twigs into the

middle of the floor. 'That's the sum total of our fuel, and it isn't worth

burning for the five minutes' heat it will give us. So we'd best resign ourselves

to the prospect of a cold night, and a hungry one unless you've got food.'

He looked at her, raised fiercely querying brows, and she shook her head.

'I was carrying nothing. You saw that for yourself.'

A disparaging grunt was her only answer, and he moved to the second chest.

'At least there are two blankets, if the moths haven't been eating better than

we will. Here.' He flung a bundle; she fended it off reflexively and it dropped

to the floor at her feet. 'Best get those sodden clothes off and wrap yourself,

or you'll have the wet-fever to contend with by tomorrow.'

Her expression collapsed into dismay and she said, 'Here? Now?'

'Here, now. Yes.' Then his mouth twitched in a hard smile. 'Don't worry, I

won't watch you. I doubt you've got anything to display that I haven't seen

before.'

Before she could react to that he had turned his back and started to strip

off his own garments without any ceremony. Hastily she swung round and unfastened

her cloak. Under it she was surprised to find herself wearing clothes that

by rights should have been a man's; trousers and a loose-sleeved shirt with

a jerkin, unbelted, over it. The revelation was startling, for until this moment

it hadn't occurred to her to notice her apparel. The fabrics were coarse, and

a flicker of memory went through her mind like the lightning flickering outside.

They had taken her own clothes away from her and dressed her in these, because…

But the because didn't come to her, neither did their identity. More conundrums;

the mystery grew more entangled. But she was learning, slowly, to bear her

ignorance and be patient. It would come back, in time.

She undressed as best she could with the cloak still on her shoulders, not

entirely trusting the truth of his last disparaging remark. Once, she couldn't

resist the impulse to glance covertly and very swiftly at him, to see if he

had lied and was watching her. He wasn't, but she caught a glimpse of his naked

back view. Very lean. Thin, almost; as if he hadn't eaten a sound meal in a

long time. But his body looked strong and sinewy, and well proportioned. Narrow

hips, long legs. Small, shining runnels down his back where his hair, darkened

to the colour of soiled straw by the rain, was dripping. And on his right arm,

just above the elbow, he wore a band made from some kind of bright metal, with

the device of a crown on it. The overall impression was brief but profound,

and embarrassed, she returned her attention to herself.

At last they were both wrapped in blankets, and she sat down a little uneasily

on the hard bed while he took the stool beside the table. Now he was watching

her and she refused to meet his gaze, said nothing, waited for him to break

the hiatus, if he intended to.

At last he spoke.

'Well. As it seems we'll be here until dawn at least, you'd better tell me

your name so that I can address you if I need to.'

Her head lifted; with the gesture her hair flicked across her cheeks and she

realised that it was short. She wasn't sure of its colour—dark, possibly

black, though it was now so wet that that impression could be misleading. But

it had been cropped. And that didn't fit with her instinct about herself. .

. Then the frisson passed and the dilemma posed by his casual question came

back to the fore.

She said, 'I . . . would rather not say.'

His fair eyebrows went up. 'Rather not? Why? Is your Fellowship so high-ranking

that you fear I'll hold you captive for an unhealthy ransom?'

Fellowship? She was baffled by the term. Then she saw that his eyes and mouth

betrayed sarcasm behind the words and she felt the skin of her face prickling

with chagrin.

She said, 'I don't know what a Fellowship is. In fact I've no idea what you

mean, because I . . .' ah, damn him! She met his steady eyes and finished,

'Because I don't know who I am. Not even my name. I—seem to have lost

my memory.'

That did surprise him, and in a perverse way she found his surprise gratifying.

A lapse; a crack in the wall of his supercilious confidence. But it lasted

only a moment before the cool mask was back and he asked simply, 'When?'

She made a vague gesture with one hand. 'Not long before you found me—I

think.' A shake of her head; water spattered from her hair onto the blanket.

'The first thing I can recall is walking on the moor, and the storm beginning.'

She frowned. 'I'm afraid of lightning.'

'Afraid of lightning.' He considered that for a few moments. 'So are a good

many other people; that tells us nothing worthwhile. So; you simply found yourself

walking, alone at night in the middle of nowhere.'

She nodded. '1 think I must have been unconscious. Before, I mean.'

'Then you woke, and started out along the track before you came properly to

your senses? It's possible, yes. But you've no thoughts of where you might

have come from or where you were going? No images, no glimmerings?'

'No,' she said. She didn't want to tell him about those, and before he could

ask any more questions she took refuge in one of her own. 'But if I know little

about myself, I know even less about you.' She ventured a small smile. 'I would

at least like to be told the name of my saviour.’

An odd light gleamed briefly in his eyes at the word saviour, but then he returned

the smile, though his had a hard edge. 'It's Grendon.'

'Grendon.' It might be a common name or a rare one; she simply didn't know.

'Then I thank you, Grendon, for what you did.' She paused. 'Though I find it

hard to guess why anyone should be riding alone at night in this weather.'

The smile faded. 'My business is entirely private, and I'm not in the habit

of discussing it with friends, let alone strangers. I accept your gratitude,

and I've told you my name; but your curiosity can stop at that.'

Stung, she looked away. 'I didn't mean to pry.'

'I'm glad to hear it. Because the fact that you're in need of help and I'm

not gives me a far greater right than you to ask questions and expect to have

them answered.' The hard smile twitched again. 'Where possible.'

'Very well. I take your point, and I apologise.' His tone angered her somewhere

very deep down where she couldn't take a proper hold of it, and she added under

her breath, 'As might you, for making your point so rudely.'

She hadn't intended him to hear that, but he did, and rose suddenly to his

feet. 'Rudely?' The word snapped out. 'I beg your pardon, madam! But I'd remind

you that this situation is of your making, not mine! When I set out on my business

I had no intention of being distracted by someone else's problems, and no desire

whatever to waste the remainder of the night sitting in this tower. Quite frankly,

you're a nuisance!'

Her cheeks flamed furiously and she stood up, almost throwing the blanket off

before she remembered that she was naked beneath it. Snatching dignity and

the blanket back she said savagely, 'Then I won't put you out any further!'

and started towards the door and the stairs beyond.

His voice stopped her in mid-step. 'Don't be ridiculous!'

She looked over her shoulder. He had shut his eyes and was pinching the bridge

of his nose between thumb and forefinger. He looked extraordinarily tired.

'I'm sorry,' he said. Clearly it took an effort to force the words out. 'What

I said was churlish and unnecessary; I apologise for it. Whatever impression

I might have given, I'm not quite so callous as to be entirely indifferent

to your plight. Sit down.' A hesitation. 'You're in no fit condition to leave,

and if you'll only believe a selfish motive, I don't want your death from exposure

or fright or both on my conscience for the rest of my life.' His hand fell

away from his face and his eyes regarded her wearily. 'Please.'

The word, the small courtesy, dissipated her anger. Even if he didn't mean

it he had at least said it, and her shoulders relaxed a little. 'Very well.'

A shrug; the wet ends of her clipped hair made new dark stains on the blanket.

'I've nowhere else to go anyway.'

For a moment tension persisted. Then he smiled. It wasn't entirely a renouncing

of his irritation, and it certainly wasn't a submission in any form, but it

put them on a marginally kinder footing.

'Well, we've reached one small understanding,' he said, and the edge in his

voice was lessened just a little. 'One obstacle overcome. Shall we tackle the

next, and see about our sleeping arrangements?'

She couldn't decide at first whether she was more afraid of going to sleep

or of staying awake. Wakefulness meant awareness of the storm, and though the

shutters at the tower windows were sound there were enough cracks and knot-holes

in the wood to make the lightning all too visible. He wouldn't allow her to

leave the lantern burning; there wasn't enough oil in it for such profligacy,

he said, and as he couldn't conjure more out of thin air she would simply have

to endure the flickering dark. Sleep, then, would take that fear away. But

there was another fear to which sleep only added extra potency, for the room

had just the one bed. One of them could have spent the night on the floor,

but there would be small prospect of any rest. Besides, one blanket apiece

wouldn't be enough to keep the cold from settling into their bones. The logical

solution, as Grendon pointed out, was for them to share the bed, with both

blankets on top of them, and let propriety be damned. And, he added, if she

imagined that his desire or intention was for anything other than a night's

sleep, she was wrong.

Which was all well and good, but she couldn't bring herself to trust it. Words

were easy; he had a clever tongue, and something—instinct, intuition,

possibly even bitter experience which she couldn't now remember—urged

her to distrust. But Grendon's will was stronger, so they settled at last,

back to back and at as great a distance as the bed's width allowed, and she

shut her eyes, burying her face in the thin pillow and trying not to let weariness

overcome her.

For all her nervous suspicions she did sleep, and what woke her was not the

danger she had anticipated, for suddenly, breaking into an uneasy dream, a.

segment of her memory came back.

She sat up in a flurry, eyes wide as she stared into the dark. Her name was

Sefira. It had come to her as though a voice had spoken it in her mind. Sefira.

And with the name another memory had returned, which sent a shock through her

as though someone had stabbed her in the stomach and then twisted the knife.

The closed, fast moving carriage and the captors who intended to kill her.

But they were not murderers. She was.

She had been on her way to her own execution.

The silence that seemed to enclose the tower like a shroud was broken abruptly

as Sefira began to breathe. She hadn't realised that she was holding her breath

but now the sound intruded harshly; a rapid, hectic rhythm. She had killed

someone. Murdered someone. And had been condemned to pay with her own life.

But. . . she didn't feel like a murderer. It wasn't right. How had she done

it? Poison? A knife? A blow to the skull? She wasn't capable of such things!

And who was her victim? What had her motive been? Was she guilty, or had there

been more to the matter; a mistake, or a conspiracy of some kind? Had someone

else had a reason for wanting to accuse her, and what could that reason have

been?

A faint shiver of lightning came through the shutters and showed a momentary

glimpse of Grendon beside her. He was sound asleep, his hair drying patchily

and one arm hanging loosely over the edge of the bed. Suddenly panic began

to rise in Sefira's mind as she saw for the second time the metal band around

his biceps. The crown symbol. Crowns were worn by kings. . . did this mean,

then, that Grendon was in service to the ruler of this country? If it did,

she was in great danger, for a king's man would be a man of justice and law.

And a murderess—her name and description perhaps already posted abroad—was

the ultimate lawbreaker.

She must go. Whatever her fear of the storm, the terror of being unmasked was

far greater, and if Grendon should have the smallest inkling of her circumstances

she had no doubt of his response. She had been condemned once; she would not

risk that horror again.

Her clothes lay on the floor where she had discarded them. They were still

wet, but no matter. Should she take his horse? She decided against it, for

that would give him reason to come after her and, besides, she didn't know

whether or not she had ever learned to ride. The storm was further away; the

interval between the last flash of lightning and the rumble of thunder that

followed had been a long one. She would fare well enough.

Sefira slid from the bed and padded across the floor. A swift backward glance

confirmed that her movement hadn't disturbed Grendon; she reached out for her

shift.

And froze.

Someone had spoken. For a fleeting moment she thought that the quiet and strangely

flat voice had come from outside, that there was a third person in the tower

room with them. But that impression was wrong. This had come from within her

own mind, and it was speaking to her.

'Sefi.' A diminutive of her name. Why was that voice so familiar? She raised

her head, muscles locking into a tension that she couldn't shake off.

`Sefi.'

So briefly that she was unable to grasp it, the image of a face flitted across

her inner vision. A girl's face, young, but peculiarly hollow, as if it had

no true substance.

`Sefi.'

Without knowing why, Sefira turned her head to look at Grendon again. Her eyes

had grown used to the darkness now and he was visible as a dim shape in the

gloom. His hair looked bleached and colourless. His arm still hung over the

bed's edge. Something was happening to her, for she was no longer afraid of

him, or of what he might do if he were to discover her secret. He wasn't an

enemy, nor was he her saviour, nor even merely a stranger to whom she had taken

a dislike.

He was a victim.

In her mind, on a level which she could neither comprehend nor combat, the

small, toneless voice spoke again.

'Sefi, I'm hungry. Feed me, Sefi. Strengthen us.'

So softly that there was no danger of waking Grendon, Sefira retraced her steps.

On a reflexive level she was aware of her limbs moving, of climbing on to the

bed and sliding carefully, adroitly across it until she was crouched over him.

His arm looked pale, limp, vulnerable. He was breathing shallowly and evenly,

so deeply sunk into sleep that he would not know what was happening until it

had begun. And then it would be too late.

'I'm hungry, Sefi . . .'

Her fingers curled around Grendon's wrist, lifted it clear of the blanket.

Very gently, she lowered her head…